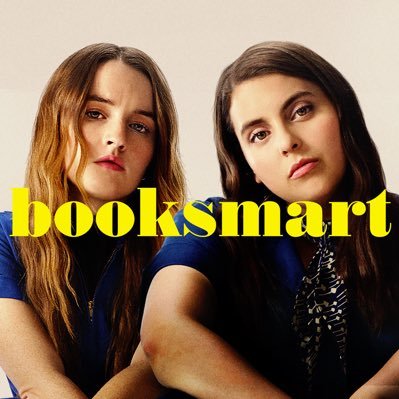

Booksmart Review

Grab a Seat

Book Smart

August 5, 2019

By my own admittance, I have never been a fan of the teen high school comedies. I feigned a few laughs while my friends reveled in the genius of “The Breakfast Club,” made up excuses when my brothers turned on “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” and only made it halfway through “Superbad” before retreating to my room to read a book. When I was in high school, I craved an escape from my daily life: not a reflection of it. Once I finished high school, I wanted to distance myself from it as much as possible. Watching teen movies felt like backpedaling into those messy years.

I steered clear of high school movies until I saw “Booksmart”. I’m glad I broke my oath because the film offers an evolved viewpoint on high school that I haven’t seen in previous renditions. “Booksmart” refuses to cash out on easy humor by playing off of cliché high school stereotypes; rather, it treats its characters as complex human beings who live in an often silly and senseless world. “Booksmart” rocks in part because it shows that teen girls cannot be labeled.

“Booksmart” boasts another rare representation in its protagonists: queerness. The way that Amy ogles skater-girl Ryan, gushes over her cuteness and then stumbles awkwardly when she attempts to actually talk to her are remarkable only in their near identicalness to every other crush in every other teen comedy. “Booksmart” does not seek to glorify queer identity, but rather accepts it as a normal way of being. It is rare to have two female protagonists, let alone queer ones. However, their story is so engaging that as a viewer I was left to wonder why on earth there isn’t more representation.

Molly and Amy defy teen movie clichés again with their bold self-assurance. Whereas many characters in the genre start with diminutive self-worth that builds as through the trials of the film, the “Booksmart” girls know exactly who they are from the get-go. They are staunch feminists—Amy’s car is plastered with “Nasty Woman” and “Elizabeth Warren 2020” bumper stickers; academically gifted—Molly is going to Yale for college and Amy to Columbia; and perhaps most importantly, they are fierce friends. The dynamic that Feldstein and Dever create between the friends is at once silly, playful, and infused with a deep love for one another. When they learn that some of their less dedicated classmates also got into Ivy League schools, they decide to give up their oath of solemnity and party at the end of their senior year. They don’t do it as a gesture of shame or of conformity; they do it to give themselves the best high school experience they possibly can. It is refreshing to see young women who love themselves and make choices out of this self-love.

The film paints Molly and Amy in a kind light, but it does not stop there. “Booksmart” insists on being kind to virtually every single character it introduces. Gigi, the “weird rich girl,” is sweet and maternal to her friend Jared. Jared, the “spoiled rich kid,” struggles to make friends. Many of the “jocks” got into Ivy League schools, and so did “Triple A,” the school’s “slut.” “Booksmart” simply refuses to take people at face value. This may be the most rewarding part of the film—as a lesson for both its protagonists and its audience.

“Booksmart” owes its generosity to its writers— Susanna Fogel, Sarah Haskins, Katherine Silberman, and Emily Halpern—as well as its director, Olivia Wilde. The all-female team proves to be another anomaly in Hollywood. But they do not use their platform to create a “Girls versus boys” mentality. They merely create a world where everyone has a seat at the whimsical, whacky table.