Remember the removal: bike ride, ASB program

The “Remember the Removal” annual bike ride is a 900-plus mile long ride and tends to take about three weeks to complete. The riders retrace the northern route of the Trail of Tears through Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas and Oklahoma.

April 12, 2017

The Alternative Spring Break (ASB) program at NEIU offered 10 students the opportunity to volunteer for Habitat for Humanity while learning a bit of the Cherokee lifestyle from educator Travis Wolfe in Tahlequah, Okla. All ten of us, along with our Student Leader Steven Cristi and Advisor RaeJoyce Baguilat, spent our evenings with Wolfe and his friends learning about historic events that impacted their way of life. If it wasn’t for the ASB program, I would have never heard about the “Remember the Removal” project.

“This (Remember the Removal bike ride) was the catalyst for me getting more involved with my language and culture,” Jacob Chavez said, a 19 year-old one-fourth Cherokee who partook in the Remember the Removal project bike ride in the month of June in 2014. “Before, I never really paid much attention to it.”

The Remember the Removal bike ride first started in 1984 with Chavez’s dad, Wilbert Chavez, being one of the first riders. Wilbert would talk to Chavez about his experience riding along the Trail of Tears, which encouraged Chavez to endure the journey as well. He applied through the Education Department within the Cherokee Nation to be one of the riders elected by their committee in 2014. Applicants must meet the age limit –16 to 24 – and pass a physical. However, an interview process was implemented in 2015. 20 riders were selected, one of them being Chavez, only 17n then.

Reflecting back on the Remember the Removal bike ride, Chavez’s perspective on his experience fluctuates.

“Sometimes you’re exhausted and can only think about pedaling,” Chavez said. “Other times, you try to imagine what it was like for thousands of Cherokee who didn’t know where they were going and being forced to walk. They were scared, sick, hungry and probably angry.

“It definitely helped me to understand where I came from and how strong my people are.”

What amazes me is how little information I received from my Lane Tech High School education on indigenous people. Learning in depth about their culture is considered extra-curricular in college, instead of required.

My ASB group heard about The Trail of Tears in our American history books, but briefly..very briefly. So briefly, I didn’t remember it until Wolfe, along with Chavez, talked about it after our first game of Stick ball.

“The Trail Where They Cried” is the name the Cherokee gave to the route they were forced to travel as the result of the Indian Removal Act. Mandated by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830, it’s composed of several routes the “five civilized tribes” – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole – were all forced to journey as they had to leave their homeland.

They weren’t given any time to collect many things, and some left without proper clothes and shoes. Families were torn apart, many women violated and men brutally punished for daring to protect their families. A rough estimate of 3,000 to 4,000 Natives died from malnutrition, diseases, depression and exposure.

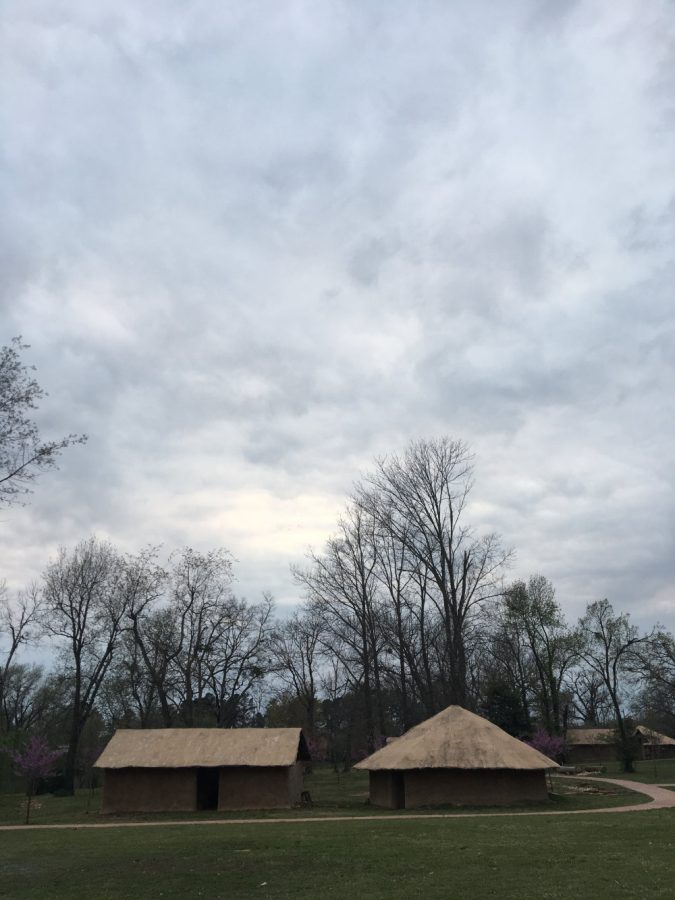

We visited the Cherokee Heritage Center where we all learned more about The Trail of Tears. We read about and saw the weapons the US troops used to violate and punish the natives – many natives were bashed on the head with them, while others were whipped for any “insubordinate” behavior. That behavior – I later learned – was often in self-defense. The deaf and blind were often targeted since they were unable to follow orders.

The Cherokee’s history with the U.S. government is full of violence and loss, yet Wolfe and Chavez shared and taught us some of their cultural beliefs and games with patience and joy. One of the games is called “Stick ball.”

We played a version of Stick ball in a large field where the men used two sticks – similar to the ones used in lacrosse, but smaller – to throw the ball at the huge poll with a fish on top of it. The women were not given any sticks, but were allowed to use any measures necessary to take the ball from the men. We were violent since the men couldn’t retaliate; they were only allowed to pick us up gently.

I must admit, when Wolfe first told us that the women were not allowed to touch the traditional sticks, I immediately raised my voice to ask “Why not?”

“Because Stick ball is violent by design; we treasure our women and do not want anything to harm them,” Wolfe said, which made almost all the women sigh in appreciation.

We learned the origin of Stick ball, which was a way tribes used to settle disputes without going to war. People died then, but the deaths of a few were preferred over the thousands that would have died in a war.

Today, both men and women play stick ball as a way to interact with each other, although there are leagues that still follow closely the older version of Stick ball.

My time with Wolfe and Chavez changed my perspective on the Native American population. It taught me that they are not just a group of people from the past, but are still very much present. They are still fighting for sovereignty, and I wouldn’t have been able to understand their struggles a little better without Wolfe and Chavez, and the ASB program.