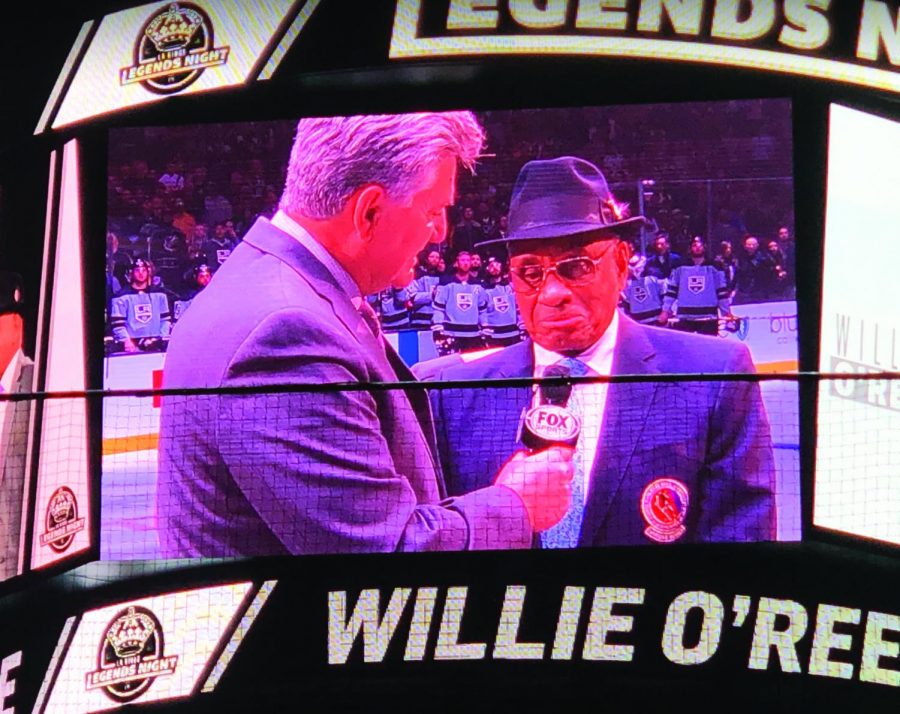

Black Athlete Spotlight: The legend of Willie O’Ree

February 25, 2020

Losing your right eye is a small price to pay to become a legend.

Harry and Rosebud O’Ree gave birth to William Eldon “Willie” O’Ree, in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada on Oct.15, 1935. While most remember O’Ree — the first black man to appear in the NHL — as a pioneer and a legend, he prefers the title of ‘hockey player.’ O’Ree and his family were accustomed to hardship; his grandparents originally fled to Canada via the Underground Railroad to escape slavery, his parents supported a family of 15, his brother’s career was cut short due to injuries and he would eventually change the world of hockey despite bigotry and, of course, his own injuries.

O’Ree began playing organized hockey at the age of five. By the age of 14, he began playing with his older brother. A year later, he was playing for the Fredericton Falcons in the New Brunswick Amateur Hockey Association. Over the next three years, O’Ree advanced through the Fredericton system, playing for the Merchants, Capitals and Junior Capitals. While playing for the Capitals, O’Ree participated in the Allan Cup Tournament, where he scored seven goals in seven games. At 19 years old, O’Ree moved to Quebec and played the 1954 season with the Quebec Frontenacs of the Quebec Junior Hockey League (QJHL), where he scored 44 points (27 goals,17 assists) in 43 games.

In his quest to prove that “hockey is for everyone,” O’Ree faced one of the greatest physical challenges of his life. While playing for the Kitchener Canucks of the Ontario Hockey Association, O’Ree was struck by a deflected slapshot that shattered his retina, broke his nose and fractured his cheekbone. O’Ree was forced to undergo surgery to repair injuries his doctors considered career-ending.

O’Ree lost 95% of the vision in his right eye that day. According to the National Hockey League’s bylaws, players were ineligible to play if they were blind in either eye. O’Ree was devastated. To protect his dream of playing in the NHL, he decided to hide his injury. He would go on to play 21 seasons, mostly in the minors, jealously guarding his secret.

After adapting to his vision loss, O’Ree went on to score 30 goals before turning professional. O’Ree made history on Jan. 18, 1958, when he debuted with the Boston Bruins.

As the first African-American in the NHL, racism plagued his entire career. Opposing fans jeered O’Ree whenever the Bruins played on the road, leveling him with racial slurs and taunts. “Besides being black and besides being blind, I was faced with four other things — racism, prejudice, bigotry and ignorance,” said O’Ree.

O’Ree condemns Chicago fans for being especially rough on him. O’Ree stated, “The fans would yell, ‘Go back to the South,’ and, ‘How come you’re not picking cotton?’ Things like that. It didn’t bother me. Hell, I’d been called names most of my life. I just wanted to be a hockey player, and if they couldn’t accept that fact, that was their problem, not mine.”

There was a memorable incident in Chicago Stadium where a Blackhawks player taunted him with racial remarks and knocked out two of his teeth. O’Ree got up from the ice to fight the offender, almost initiating a riot. Police escorted O’Ree from the building for his safety.

During an interview following an incident in February of 2018 that saw racist jeering directed at Washington Capitals right wing Devante Smith-Pelly, O’Ree stated, “I just say we haven’t really come that far, there’s still racism in the league. There’s racism in the junior leagues, the midgets and the smaller leagues. I guess we’ll just have to keep working at it.”

O’ree is often credited as the “Jackie Robinson of Hockey,” the fastest man on the ice and the king of the near-miss (a reference to the many goals he almost scored). But his greatest contribution would come off the ice. In 1998, O’Ree joined the NHL again, this time as the Director of Youth Development and hockey ambassador for NHL Diversity. In this role, he would continue to encourage children to go after their dreams. According to O’Ree, success is a choice predicated on dedication and perseverance.

“If you think you can, you can. If you think you can’t, you’re right.”

Richard Martin • Jan 25, 2021 at 12:20 pm

Bernard James there is a much larger history with the Oree family. Many of my closest family are from New Brunswick and Maine. Willie Oree and I are distant cousins. I dont even know any Orees. Our connection goes back to the late 1700s/early 1800s, the Orees are distant now, but so are many of my Canadian cousins whose ancestors intermarried around the time of the Revolution.

Are you DNA Tested?

Bernard James • Oct 13, 2020 at 4:15 pm

I rather suspect that Mr. O’ree’s family migrated from South Carolina in their search for freedom. If correct, he and his, share lineage from my great grandfather, Sidney James Sr. and wife Annie. If this information could be shared with him, I think there is a connection for Bertha James- Oree and Cary Orie of then Marion, County, SC. Now area is Florence, SC. I would love to share more with Willie or family if there is interest..

Bernard James

Bob • Jan 23, 2024 at 10:59 am

cool