Is Instagram reviving poetry or killing the genre faster?

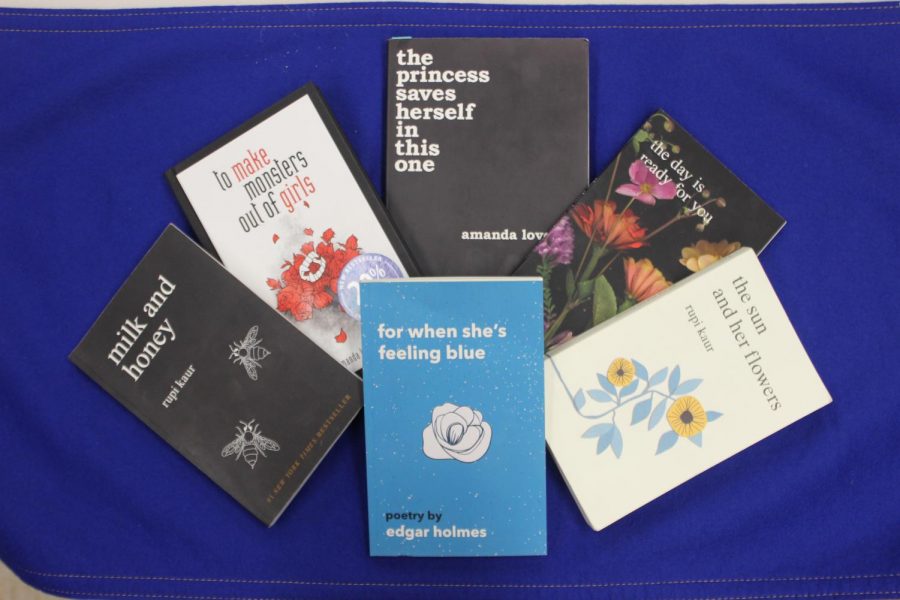

My personal collection of poetry books by “Instagram” poets who inspire me.

December 2, 2018

“Don’t ever quit your day job” is the advice I heard from an author who was visiting NEIU’s Creative Writing Intense Summer session a year ago when I took the course. The advice stood with me ever since.

As an aspiring writer I am well aware that it is a rocky and uncertain career. However, many writers are finding success through newer technological outlets such as Instagram rather than going the more traditional route. Instagram, Tumblr and other media outlets let writers instantly publish their work and share it with potentially millions of people.

Writers like Rupi Kaur, whose debut poetry collection “milk and honey” spent more than a year on The New York Times Bestseller list and stole the title of bestselling poetry book from “The Odyssey,” have managed to build lucrative careers using Instagram. Her posts reach her over one million followers and they allowed her to tour the world performing her poetry. Her recent stop in Chicago this past month sold out, a career move that many writers can only hope to have.

As an English student I am starting to discover that, despite the success that many of these writers have accumulated, the invisible hierarchy of writers dubs them in last place.

It wasn’t until I had a conversation with a faculty member in the English department that I began questioning the validity of writers whose main outlet is social media.

Melisa Rekanovic, an English major at NEIU, said “Instapoetry, poems being posted and shared on a social media platform called Instagram, is the lowest of the lows, especially for a poet who is immensely indulged in the poetry community. Readers, (who) are not writers of poetry, may praise Instapoetry for what it is, but once you enter the world of poetry, there are far more substantial forms of sharing your work.”

What is it about this type of poetry that makes other writers consider it a lower form of writing? While that answer is open to interpretation for many, for me it comes down to its extremely simplistic style and form. Often times Instapoetry is framed into what can fit into a quickly shareable image and uses simple, non-complicated language to relate a common “universal” feeling.

For many, this simple form of poetry is the problem. Poet Rebecca Watts criticized the popular Instagram poet Hollie McNish’s work as that not of a poet, “but of a personality.”

Watts said, “Artless poetry sells. The reader is dead: Long live consumer-driven content and the ‘instant gratification’ this affords.”

Despite the harsh feelings towards Instapoets, there is no doubt that they are reviving the poetry community. According to Publishers Weekly, “12 of the top 20 best-selling poets last year were Insta-poets, who combined their written work with shareable posts for social media; nearly half of poetry books sold in the United States last year were written by these poets. This year, according to a survey conducted by the National Endowment for the Arts and the U.S. Census Bureau, 28 million Americans are reading poetry—the highest percentage of poetry readership in almost two decades.”

But the criticism is still strong. Watts expressed her desire for the literary community to “stop celebrating amateurism and ignorance in our poetry.”

However for me, the real ignorance comes from the pretentious outlook that all poetry should meet a certain standard.

“The Princess Saves Herself In This One,” a poetry collection by author Amanda Lovelace, personally reignited my own passion for writing. Lovelace writes about suicide, depression and family issues in a way that allowed me to form a simple yet meaningful relationship with her words.

Her words were not high-score scrabble words. I did not need to pull out a dictionary or count the rhythming beat to get a full understanding. I simply read and was able to resonate with what was written on the paper in front of me.

The argument of capitalism is also tied into why many are questioning Instapoetry.

Olivia Cronk, an English professor at NEIU who teaches Hybrid Form Writing, said “We consume this kind of text with our eyes, in a very scrolling-ish manner. Poetry that is visually bite-sized/easy to quickly digest is more useful to the Capitalist Machine. It’s also closer to the language of advertising.”

For many, this is true. These writers are often turning their online presence into an entrepreneurship opportunity. The Atlantic said, “Social-media poets, using Instagram as a marketing tool, are not just artists—they’re entrepreneurs. They still primarily earn money through publication and live events, but sharing their work on Instagram is now what opens up the possibility for both.” Writer Cleo Wade’s poetry has been picked up by major brands such as Gucci and Nike.

While I can understand the hesitation, capitalism is not going away anytime soon and writers should not be expected to starve volunteeringly if they are given an opportunity to earn a living with their writing. If they choose to take up a deal with a brand then more power to them.

But despite the criticism that Instapoetry receives, many are praising it for giving new voices.

Dr. Eleanor Spencer-Regan, digital director of the Institute of Poetry and Poetics at Durham University, said “This is a radically democratic method of publishing that is giving opportunities to many women, people of colour, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and people who publicly disclose mental illnesses. These people are rejecting the old rules of a literary world that they feel may have rejected them.

While many have differentiating opinions on the status of Instapoets, Rekanovic still said to support all poets.

“Support your local poets! No matter how big or small and no matter what platform. What is shared to the world should be taken with a kind heart of tolerance and an open mind.”

Kevin • Jun 11, 2019 at 9:43 am

As a poet, I publish in e-book format, paperback and, yes also on Instagram. I want readers to appreciate my writing and by utilising Instagram I’m bringing my work to the attention of a wider audience. To me this can only be a good thing.