Good vs. bad borrowing: students invest in themselves

March 14, 2017

The NEIU Economic Inequality Initiative set out to teach students the value of financial literacy.

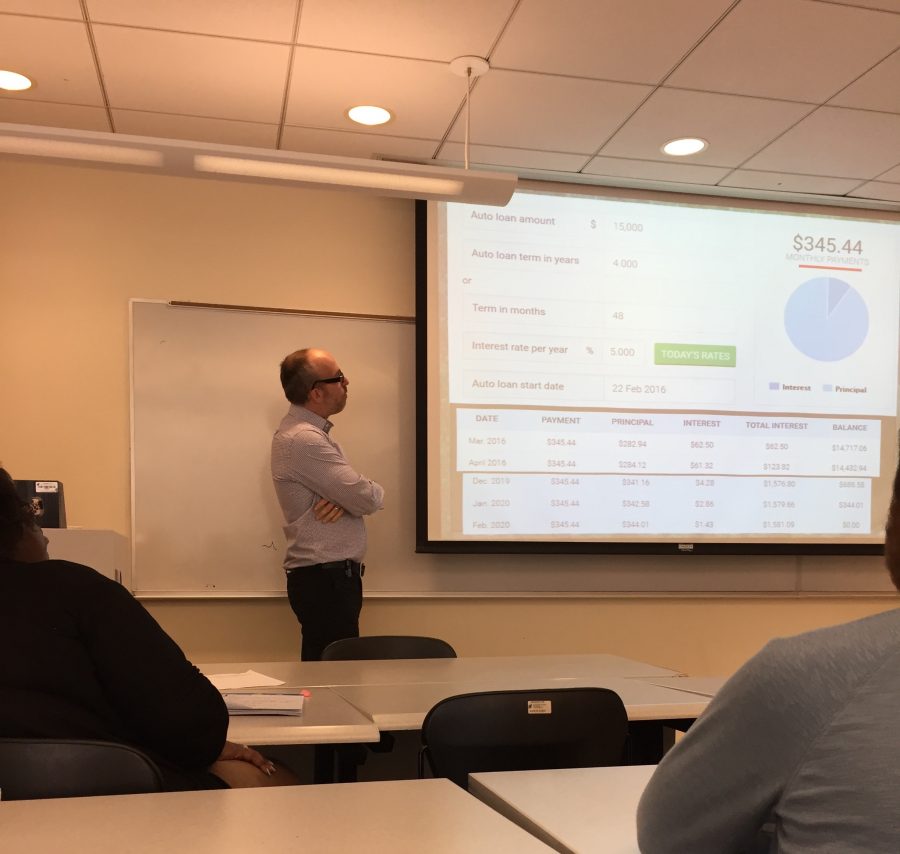

Dr. Scott Hegerty, associate professor in the department of economics, led an open discussion with students on March 7 about good borrowing versus bad borrowing, investment of borrowed monies, how to utilize credit efficiently and how to think critically about interest rates.

“How much is too much debt?” he asked. “A lot of times, people are selling you a number that’s good for them and not for you.”

Hegerty said that too much debt is probably more than a fraction of a consumer’s income that can reasonably be paid back. “Part of it is about making smart decisions,” he said. “There are a lot of ways out there to separate people from their money.”

Students answered that the right amount of borrowing depends on the circumstances and it may at times be necessary to the consumer seeking to borrow money. Hegerty explained that a borrower might want to build a history of credit, which helps consumers with future transactions such as a home or car loan.

Transactions include productive investments on such activities like earning a college degree.

“Would borrowing make the difference on doing something and not doing it?” he asked. “Does the debt increase your income?”

The answer is that it should. If a student – who at the end of the day is a consumer – incurs debt to get a college degree, their earning potential should go up. Another example is if a business takes out a loan to expand, more clients or working hours and capital should earn it more revenue to be able to pay the loan. Students can calculate their debt to income by using a ratio. As the denominator, if income grows, essentially debt shrinks.

“Any kind of productive investment can actually give you more power to pay it back,” Hegerty said and introduced a ratio students can use to figure out their debt as a percentage of their income.

He discussed how paying for food or perishables with credit cards could be hazardous to an individual’s financial health. “Unless your credit card is giving you points or rewards for doing it, pay cash for anything that will be gone by the time the bill comes,” he said.

A consumer can create a cycle of debt without realizing it. For example, if a student pays for something with a credit card that they can pay for with cash, it is easy to forget the bill until it comes. At that moment, any savings or cash on hand may have been spent and the student would then have to take money from an important endeavor, such as paying for groceries or a doctor’s visit, to pay for the credit card bill.

The open discussion lastly emphasized on the interest rate, which is the price of borrowing and adds to the responsibility of repayment on the borrower.

“The monthly payment is how people think in their budget, but it hides the actual price of the debt,” Hegerty said.

The original amount borrowed is called the principle or principle balance. When students borrow money for example to pay for a college degree, bearing in mind the interest rate on loans and possibly paying the interest off in increments helps to lower debt.

Money also moves through time because interest can also be earned on money that is invested. Examples include money held in savings accounts and Certificate of Deposit accounts. In turn, interest is paid on borrowed money in order to obtain a purchase sooner than saving money to buy it.

“There are always two sides to a price: the buyer and the seller,” he said. “When you buy something, the one thing you should look at is the interest rate. Debt can be okay as long as you do it smart.”