Researching to Remember

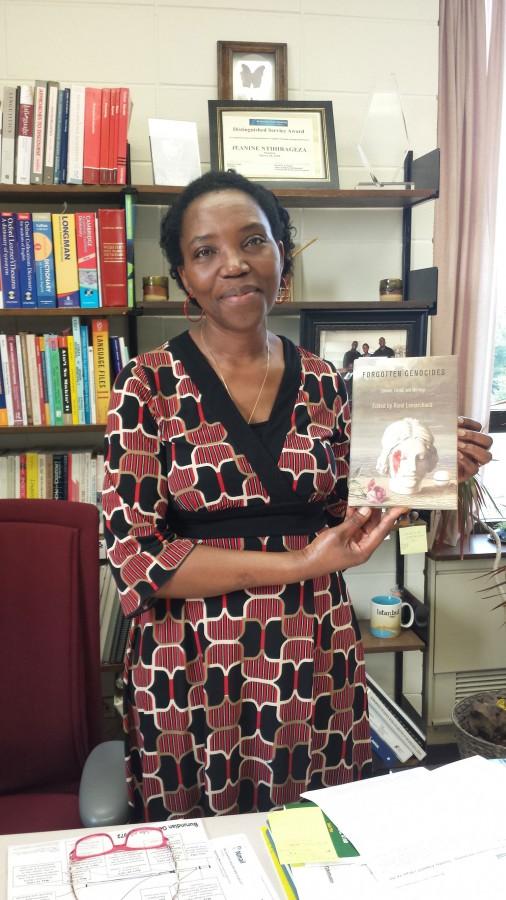

Dr. Jeanine Ntihirageza, pictured with “Forgotten Genocides,” a series of essays and analyses edited and compiled by French-American political scientist, Dr. René Lemarchand.

September 22, 2015

The Genocide Research Group

Countless crimes against humanity go unrecognized. But it’s through the efforts of today’s researchers and activists the voices of tomorrow can be empowered.

Three years ago, Dr. Jeanine Ntihirageza — an NEIU professor and the department chair of anthropology, the English Language Program (ELP), Philosophy and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) — founded the Genocide Research Group. The works of Dr. René Lemarchand, a French-American political scientist who studies African political states and ethnicities, inspired her. His essays on collective memory brought to surface the repressed memories of her childhood in Burundi.

The Genocide Research Group — a branch of NEIU’s African American Studies Program — is a collective of like-minded scholars and professionals devoted to the investigation of and response to the African Diaspora, genocide, and mass human rights violations on the African continent. It seeks to dissect the complexities of both the causes and repercussions of African genocide.

In addition to conducting research, the group fosters the promotion of genocide awareness among the academic community.

Burundi

The Republic of Burundi is a landlocked East African nation sandwiched between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Tanzania. The country shares its northern border with Rwanda. Geographically, it is close to the size of Maryland.

Burundi is home to roughly 10.7 million people and its population is divided into three distinct ethnic groups: Hutus, who make up around 85 percent; Tutsis, accounting for 14 percent; and Twas, who represent one percent of the Burundian populace.

Dr. Ntihirageza was 11 years old in 1972, 10 years after Burundi had gained its independence from colonial Belgian rule, when ongoing ethnic tensions between Hutu and Tutsi populations resulted in the targeted mass killing of over 200,000 Hutu, primarily males. Business owners and intellectuals were targeted in many of these cases.

“Somehow, (during the) colonization…(the) Belgians made Tutsis feel like they were better than the Hutus,” said Dr. Ntihirageza. “So they put them in (the) justice system, army, education, all the most important areas of government — all those areas were ruled by the minority Tutsi. That’s what the Belgians wanted.

“So the Hutus revolted. When they revolted, they killed Tutsis; what’s recorded in the literature is about 3,000 Tutsis were killed,” she said. “But when that happened, the government said ‘Okay.’ So they stopped them quickly, and they started killing all the Hutu males.”

Among those executed were Dr. Ntihirageza’s brother and father.

Throughout and after the violence in 1972, the government of Burundi forbade grieving the loss of loved ones. Any display of grief was designated a crime punishable by imprisonment, seizure of material values, or execution.

“We were told you don’t mourn, you don’t grieve,” Ntihirageza said. “If you did, you would be reported. They would take you, and you wouldn’t come back.”

Such polices have effectively aided efforts to mask organized mass murder and other crimes against humanity.

The Genocide Research Symposium

The third annual Genocide Research Symposium, hosted by the Genocide Research Group, will be held in NEIU’s Alumni Hall Nov. 10. During the morning sessions, researchers will present their findings related to diaspora in African regions in a series of talks.

These will be followed by an address by keynote speaker Dr. Christen Smith, a polymath researcher of African studies who received her doctorate in cultural and social anthropology from Stanford University.

In the afternoon, the symposium will focus on activism. Representatives of the Black Lives Matter movement will hold an information session on the day of the symposium.