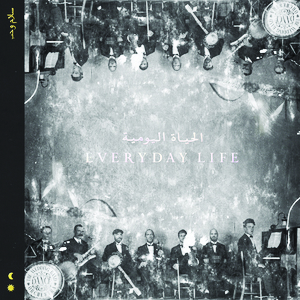

Coldplay’s ordinary ‘Everyday Life’

Coldplay has been around since 1998

December 3, 2019

Coldplay’s fall from grace has been cold and swift. Once celebrated for their bold exploration of progressive rock, Coldplay has been relegated to Nickelback status–ruthlessly ridiculed without any tangible reasoning behind it.

Coldplay’s evolution from angelic melodies to stadium rock was welcomed with a reluctant enthusiasm. The Chris-Martin led quintet out of London deviated away from their comfort zone, embracing the natural progression that inevitably accompanies fame and popularity. And for a while, it worked.

But somewhere along the way, Coldplay fell out of public favor. Perhaps perception shifted after Coldplay was upstaged by both Beyoncé and Bruno Mars at the 2016 Super Bowl Halftime show. Perhaps Coldplay’s audience became fatigued by experimentation, longing for a return to the formula that made Coldplay a fan favorite.

“Everyday Life,” Coldplay’s eighth studio album, isn’t going to engage listeners disenchanted by Coldplay’s new direction. The London-based prog rockers struggle to identify a happy medium between their desire to appeal to the masses and goal of promoting a politically conscious message. Previously defined by vague expressions of emotions that invited listeners to inject their own personal experiences, Coldplay’s clumsy attempt to touch on culturally relevant topics falls flat. In a political climate infected by pointed rhetoric, hateful slogans and general incompetence, lazy messages of camaraderie–”Arabesque” is simply Chris Martin repeating that we have the same blood–are not enough to offset even lazier composition.

Coldplay’s newfound passion for politics seems artificial. Stating that guns are bad is a political statement by default, but “Guns” failure to investigate any of the underlying causes or tragedies caused by gun violence renders the entire effort meaningless. Even those who appreciate the socially conscious identity of “Everyday Life” will have difficulty looking past the sheer lack of energy and enthusiasm.

This album is the equivalent of a midlife crisis. “Trouble in Town” and “Daddy” never progress beyond first-gear, operating as a tired, piano-driven ballad. “BrokEn” sounds like the result of a pop band attempting to penetrate the gospel market recently explored by Kanye West. “Orphans” possesses the elements to potentially serve as an anthem for the inebriated youth, but an uninspired chorus atop mundane instrumentals drags the entire song down.

The only redeeming factors aside from the Jonny Buckland’s mildly catchy riff in “Arabesque” are “Champion Of The World” and “Everyday Life,” the album’s penultimate and closing tracks. “Champion Of The World” is a pointed narrative of the failures and subsequent perseverance that precedes success. Martin expertly describes the leap of faith required to remain unencumbered by frustration and defeat.

“Everyday Life” depicts the shared-yet-unique pains that we all endure. Martin prompts his audience to abandon vendettas and embrace the commonalities of the human race, asking, “How in the world am I going to see you as my brother, not my enemy?” Nevertheless, neither “Everyday Life” nor “Champions Of The World” are everyday listens.

I wanted this album to make me feel. I wanted to rediscover the celestial sound that propelled Coldplay to the top of the charts. I sought the inspiration and pensiveness that I associate with Chris Martin and Co. But I never got it. Instead, I heard a band fumbling for an identity, sterilizing their music in an effort to recruit fans who didn’t appreciate their previous art. This album isn’t for fans of any one genre. It’s inoffensive yet unremarkable, a forgetful experience for all rather than meaningful listening for a few. Give this album a shot, but temper your expectations.

J Willis • Dec 6, 2019 at 5:58 pm

What an inane bunch of BS masquerading as a review. Stick with sports Matt. Music is obviously not your strong point. Hip hop & rap fans like you will never like music on the level as Coldplay.

Managing Editor • Dec 6, 2019 at 10:42 pm

Not a rap or hip-hop fan, as evidenced by my entire catalog. Thanks for commenting.