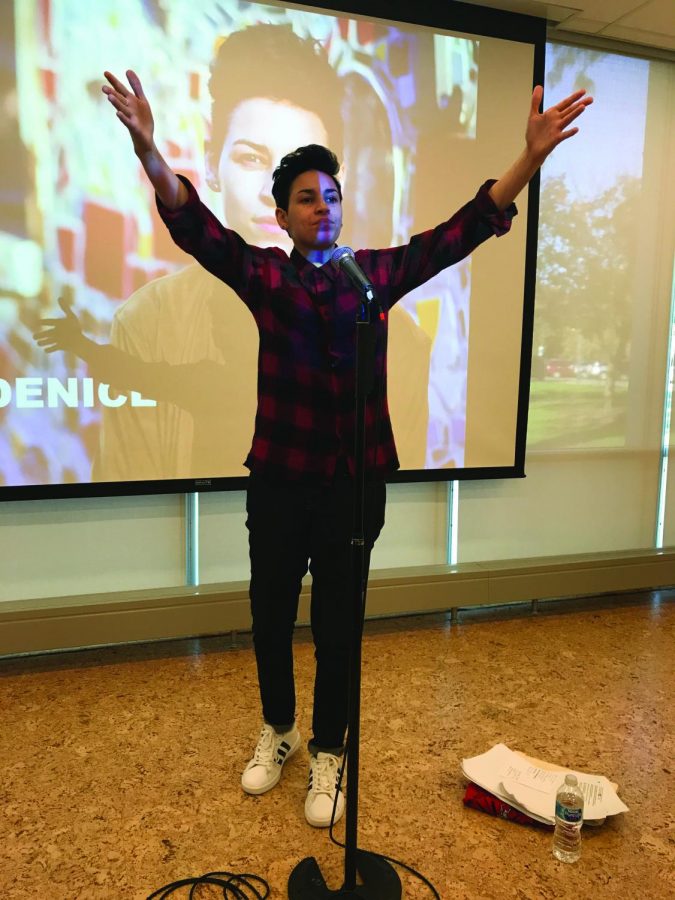

Embracing ‘Accents’: Denice Frohman

Cecilia G.Hernandez

Some of Denice Frohman’s poems can be found on her website, denicefrohman.com. She is currently performing on several other campuses. She is scheduled to appear at Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA on Nov. 2.

October 31, 2017

In her red plaid shirt and black jeans, Denice Frohman passionately and comedically recited her poem “Accents” in the Angelina Pedroso Center on Oct. 17.

Frohman shared with us how her mother’s accent “got too much salsa to sit still,” and something in me clicked. Growing up with a Spanish-speaking mom, I wished her accent stood still, invisible to the English-speaking world so that she wouldn’t be a victim of racism.

That is why we need more poets like Frohman, to remind us accents are beautiful; they are evidence of their owner’s hard journey to the U.S., and not an excuse to degrade the people that helped build this country.

When Frohman recited “English sits in her mouth remixed. So ‘strawberry’ becomes ‘estrawberry’ and ‘cookie’ becomes ‘ecookie,” I remembered the times I would try to teach my mom the difference between saying “tree” and “three.” We would spend ten minutes saying the two words over and over again, always ending in laughter because my mom would always say “tree.”

I remembered I loved and hated her for saying “tree.” It was as if her accent was my constant reminder that she was vulnerable to others.

She was a neon-yellow target for belittlement and bullying, something she experienced everyday living in this country.

I recall one vivid memory, one where I was about to punch an employee for harassing my mom in the two seconds I was away. She was yelling at my mom to pick up several sweaters she thought my mom had dropped. In her haste to find the English words to explain it wasn’t her, my mom didn’t realize the employee’s body language promised violence.

I heard my mom repeat “me, no do” before I pushed between the employee and my mom. The employee immediately backed off after I arrived.

Encounters like these are not unfamiliar. Because of my mom’s accent and appearance, many racists see the opportunity to harass her, not knowing I’m not too far behind to protect her.

My mom used me as her translator since I could speak, dragging me along to banks and doctor appointments because she knew Spanish-translators were scarce and often pressed for time.

However, I was more of a buffer between her and the English-speaking world. I was the person other people needed to go to first before they reached her, and the first my mom spoke to in order to communicate with others.

I grew up with fear since I knew people would try to take advantage of my mom. I became anxious when she went anywhere without me, and I developed a short temper with anyone that expressed annoyance towards my mom’s “broken” English.

I resented her for her accent, for not blending in. I wanted to erase any and all evidence of her alienness since I truly believed she was the one that had to fix herself.

I think my mom saw this because, soon after, she started taking free English classes at Truman College. Little by little, she could finally say “three” within a complex sentence, her accent still audible and bold, but I realized my mom didn’t need fixing.

What needed fixing is this idea that there’s only one “American” accent, and anything other than that is wrong or broken.

Now there’s no telling my mom to be quiet because, as Frohman says in her poem “Accents,” “she doesn’t know ‘quiet.’”

She defends herself proudly while I gaze at her admiringly.

Frohman’s poem reminded me how my mom’s accent is a part of her and will always be loud. Instead of wishing it would sit still, I embrace my own.

“Her accent is a stubborn compass, always pointing her towards home.”