Behind closed doors: The unique nature of transgender domestic violence

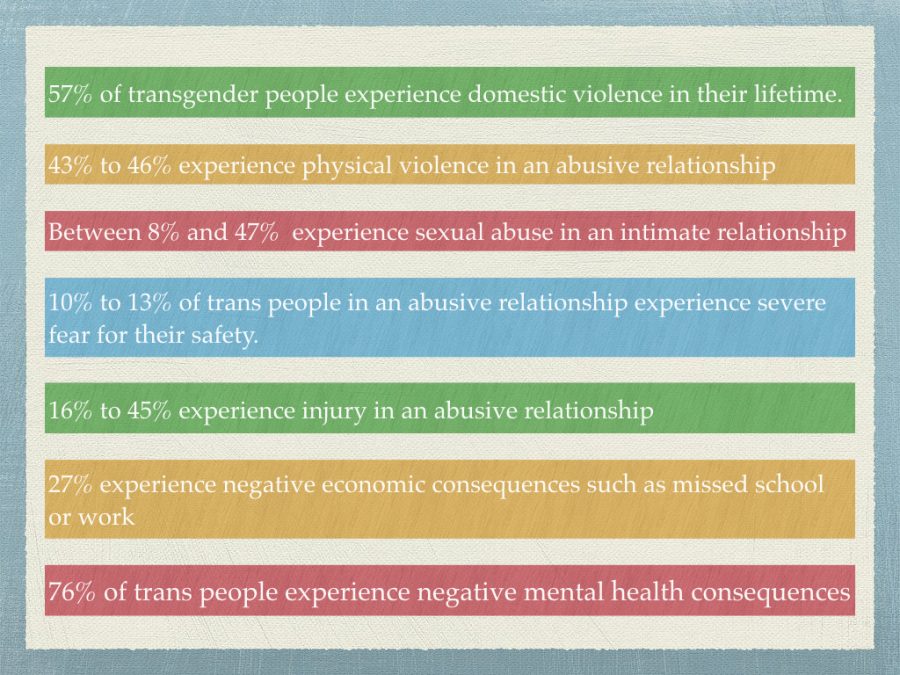

Dr. Messinger says the wide range on some of these statistics is due to problems with sampling during research.

April 12, 2017

NEIU hosted a panel on March 29 titled “Transgender Domestic Violence: Developing New Strategies to Assist Survivors.” The panel included Dr. Jessica Punzo, director of the “Anti-Violence Project” at the Center on Halsted, and Dr. Adam Messinger, assistant professor in the NEIU Justice Studies Department and Women’s & Gender Studies Program.

During the panel, gender identity was explained to be someone’s internal perception of their gender regardless of their sex assigned at birth. A transwoman was defined as “someone whose sex assigned at birth was male but whose gender identity is female,” and transman was defined as “someone whose sex assigned at birth was female but whose gender identity is male.”

“When we say (transwoman/transman) globally it doesn’t mean that someone has to have surgery or take hormones. It’s just about someone’s internal perception,” Punzo said. “So we get a wide range of what someone who is a transwoman might look like, or might act like.”

Since these terms are defined differently by researchers it makes for varying numbers on domestic violence in trans communities.

However, Dr. Messinger recently reviewed the literature available on the topic for his new book “LGBTQ Intimate Partner Violence: Lessons for Policy, Practice, and Research” and found surprising trends in statistics.

There are many similarities between domestic violence in cisgender (when the sex assigned at birth matches an individual’s gender identity) and transgender communities, however there are many unique traits to transgender domestic violence.

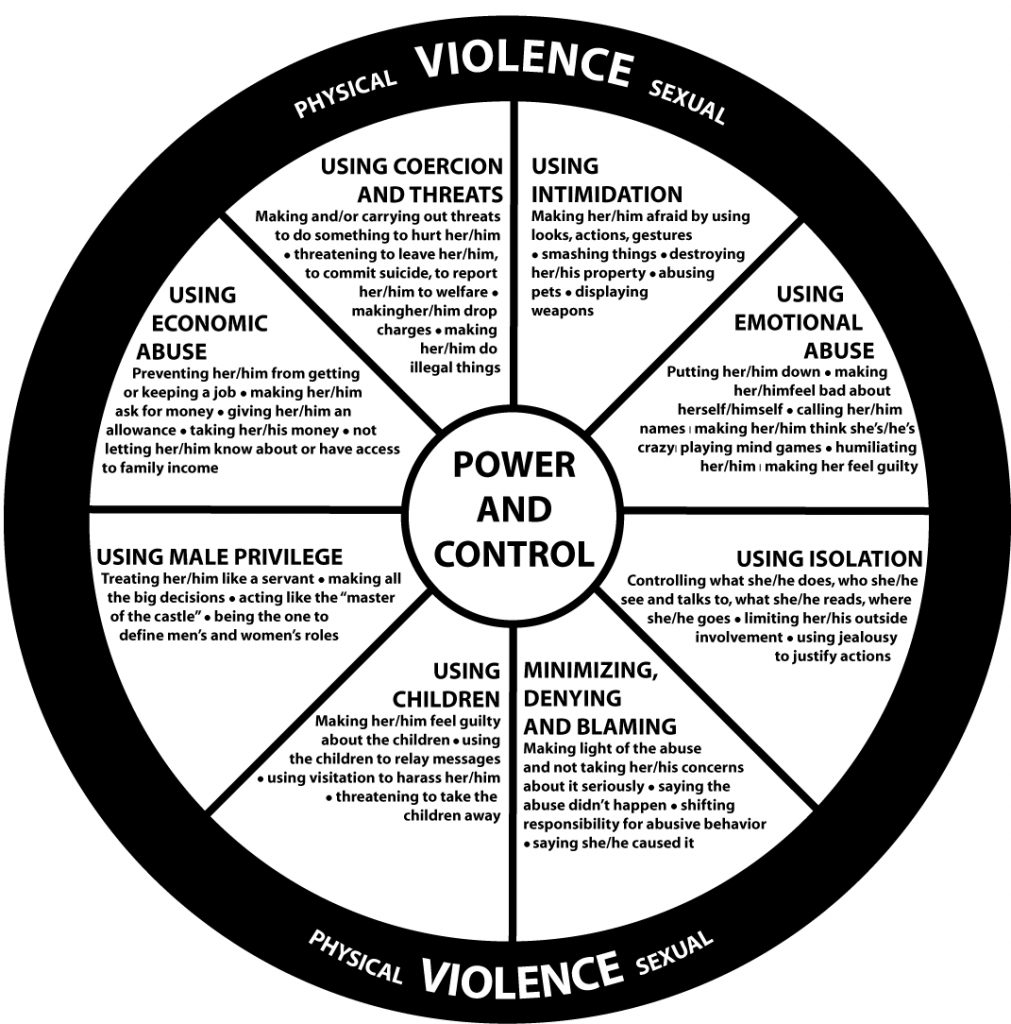

Abusers of trans victims use additional tactics to hold control over their victims.

“Research suggests that many trans victims of domestic violence are often forced to remain closeted about their gender identity or about being trans,” Messinger said. “(The abuser) might threaten to out the victim in terms of their gender identity or their trans identity.”

Punzo described some of the unique threats that transgender victims hear. “An abuser might use power and control to say ‘If you don’t do what I want, I’m gonna out you to your boss,’ ‘If you don’t have sex with me, I’m gonna out you to your family.’ The implications for that are quite serious because, as some of you might know, there are not a lot of protections for trans people.”

She also said in many states you can still be fired for identifying as trans.

Other unique traits of transgender domestic violence included refusing to use gendered pronouns, gender identity, or name the victim prefers, forcing them to wear or not wear certain clothing, denying access to hormone therapy treatments, and using verbal slurs and transphobic slurs. The panel referred to these as “micro-aggressions.”

The panelists detailed some of the distinct sexual violence that trans victims experience. “Often times, the controlling mechanisms that abusers use on trans victims directly relate to questioning if someone is really the gender identity that they claim,” Messinger said. “‘You’re not man enough.’ ‘You’re not woman enough’ and that type of accusation can play out in sexual violence as well. ‘If you’re a real man, real men like rough sex.’ ‘Real men don’t say no,’ and so many victims who have been interviewed talk about that in order to prove to their partner and to themselves that this is truly who I am, that this is my gender identity, they were coerced or forced to do sexual acts that they wouldn’t have done otherwise.”

On top of that, transgender victims face difficulties receiving services for their abuse.

“A lot of domestic violence agencies don’t have the capacity to work with trans victims,” Punzo said. “The domestic violence movement came out of the feminist movement, and the thought that (domestic violence) was a woman’s issue. But we know that’s not the case.”

Punzo also pointed out that there are only two places in the Chicago area that trans women can go to seek shelter. Many shelters don’t accept trans people, voicing concerns about retraumatizing cisgender people in the shelters.

Punzo noted that trans people often have difficulty identifying themselves as victims since much of the marketing material and handbooks that DV organizations use feature males as perpetrators of abuse against women.

The panel also discussed ways that shelters can improve access to services for transgender victims.

“One of the barriers to providing services to trans people is the notion that there aren’t enough resources, there’s not enough beds to go around in shelters, there’s not enough funding to hire more counselors, they’re constantly being squeezed dry by the federal government so we can’t design more services. To that I would just say, it’s not a problem of lack of resources,” Messinger said. “If you have trans people receiving resources, it’s just a matter of adjusting services that you provide to them. It’s not enough to just say that ‘we have an anti-discrimination policy, we accept everyone.’ It’s let’s go the next step and actually provide services that recognize the unique nature of your abuse. Let’s discuss the unique barriers and internalized transphobia and other issues in your life that make it more impactful on you, but let’s tailor our services. That doesn’t necessarily require a whole new set of hiring or whole new funding sources.”

The panel addressed controversial issues as transgender rights are in dispute across the United States, from access to public bathrooms in North Carolina to high school locker rooms in Palatine. Messinger summed it up best: “We fear what we don’t know.”