Back to School 2014: Inequality Continues

September 9, 2014

More than a year removed from the closing of 50 schools, Chicago Public School (CPS) students are back in class this week. After the largest mass closures of public schools in American history, CPS schools are still faced with budget cuts this year.

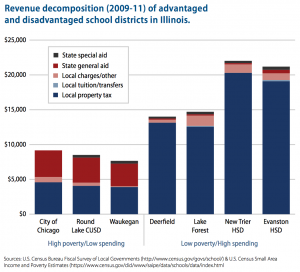

Chicago is a pretty firm example of unequal public school funding. If you compare CPS schools with the surrounding suburban school districts, there is a substantial difference in funding per student.

The urban public schools receive additional funding from the state, but the taxes on wealthier suburban properties can more than double the funding per student for CPS.

For a point of reference, students in New Trier and Evanston Townships both receive more funding per student than it costs the Illinois Department of Corrections to incarcerate an inmate for an entire year ($20,146). That’s nearly enough funding to attend NEIU for a year ($21,929 estimated cost attendance 2014-15).

Even with unequal public school funding, schools from poor and affluent areas are expected to display acceptable standardized test scores.

Schools in affluent areas treat the test scores with minimal concern and their students meet the standards without pressure on teachers and faculty. These schools focus more on critical thinking skills and problem solving exercises.

In CPS schools, test scores and getting students to show up have become the primary focuses of school operations. In many cases, teachers and faculty have been fired for their students’ failure to meet the desired test results. Or whole schools can be shut down for underperforming and under-enrollment.

Beyond the process of unequal funding, maybe we should question the actual concept of the American education system.

What is the academic motivation of American public schools? Perceivably, it is to set academic standards of results and pressure teachers to motivate students so they can illustrate their competence in meeting such standards through testing.

This concept doesn’t adequately explain how children are learning anything other than how to display uniformity and repeat menial concepts. There is no structured effort that promotes rational inquiry, setting intellectual goals, self-expression, and how to cope with reality.

Let’s throw out the concept of standardized scores. Maybe we can measure the effectiveness of education by comparing prison populations with college student populations. We can quantify it with the number of jobs that allow people to have dignity and give them enough time to spend with their children.

Those are the real indicators of an effectively improved society. You can’t measure it on a Tuesday morning for a second grader. You measure it 20 years later.