You Are Not Alone: NEIU’s K(no)w More Program Offers Help to Victims of Domestic Violence

October 20, 2022

Domestic violence is a pattern of coercive control that one person exercises over another, as defined by the Illinois Coalition Against Violence. The perpetrator can include partners, family members and roommates among other people within the victim’s life.

This is a revision of the resources available at NEIU for victims of domestic violence with Annette Brandt, director of the K(no)w More program, who offered advice to people that might be looking for help since there has been a recent surge in cases of domestic violence in our communities.

As reported by The Harvard Gazette, the COVID-19 pandemic produced this spike in cases of domestic violence as people sometimes had to spend long periods of time behind the same door as their abusers, along with growing mental health issues.

“Data also suggest that a person victim of domestic violence will attempt seven times on average to leave a relationship before successfully getting away”, says Brandt. “In any of those attempts things can get dangerous and the victims of violence are most at risk.”

Brandt said that her program’s mission is to help victims of abuse to navigate a system that sometimes is difficult. She added that they channel the outcry of abuse instances into solutions for the survivors with no distinction of race, gender identification or sexual preferences.

Her program is funded by a grant from the Department of Justice’s Office for Violence Against Women, but NEIU’s K(no)w More program is trying to cover the gap in help that usually affects LGBTQ+, BIPOC and males.

At the beginning it is all about control

Often, there are repeating behaviors that add up over time. These are behaviors downplayed through the “honeymoon period”, which escalates whenever the perpetrator has gotten a concrete hold of the victims/survivors.

Brandt said that controlling a partner is the most common domestic violence scenario: “What we really know is that 90 percent or more of domestic violence has nothing to do with actual physical hands-on violence. These are all power and control tactics.”

To know more about the power and control red flags, she directs people interested to the Power and Control Wheel, designed by a team of preventers in Minnesota. The graphic illustrates the idea that emotional abuse sustains physical abuse.

Perpetrators will escalate their behaviors in order to keep control over their alleged victims. First, they will play with their emotions, making people feel bad about themselves or gaslighting them with lies.

Then they will progress into actions. Brandt said that escalations can look like “controlling what people do, where they go, who they talk to, what they read, you know, all of these things that anytime that they have involvement in anything, that person is like, tell me where you’re going, what are you doing where you know.”

Brandt says that at NEIU the most common form of emotional, non physical abuse is stalking. Brandt defines it “like a repeated series of behaviors that makes a person uncomfortable, and makes them feel threatened.” The perpetrator is “ sending the message ‘I can get to you anytime I want’.”

NEIUPD and K(NO)W More take this form of abuse seriously since they consider stalking as a precursor to domestic violence, sexual abuse and dating violence.

NEIUPD reported nine events of stalking or domestic violence on campus in the last three years although Brandt recognizes that everywhere these situations go unreported and what is in police data is just the tip of the iceberg.

Getting out before it is too late

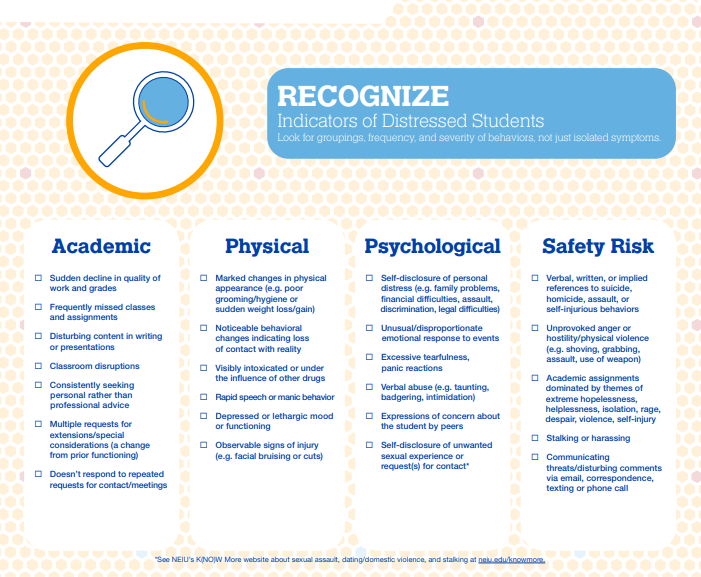

At this stage, when the victim still has not suffered instances of physical violence, help from the community and support networks are supremely important. With cases of domestic abuse, a large factor in how things escalated is due to the isolation the abuser would impose on the victim. Brandt says, “It is our responsibility as friends, as family, as community members to point it out when we see something that is troubling. We need to know the red flags, to point it out but not in a way that shames the other person.”

That does not mean that the idea is to blame the victim for not taking action. Brandt said there are many other issues that make it difficult for victims to take the help offered by friends or institutions and leave. “Once you are in love, it is hard to have good judgment.” There are consequences to every decision made, and they would need to live with it, as mentioned by Brandt.

She offered assurances that the idea of the service is to help, “We just need to keep offering our hand.” She mentioned that making a safety plan with a professional, who has some training in domestic violence, is one of the best courses of action. NEIU offers three confidencial advisers for this purpose.

Victims can suffer an escalation of violence when trying to leave a situation of control. Brandt told us the story of a man, partner to a female member of the NEIU community, that “would just put his gun by his side before starting a conversation with his partner to set the mood.”

Any attempt to dispute the situation of control by the victim could often escalate to physical violence or even death.

That is to say that not all men, who are the common perpetrators, are like this: “We, in this movement, have been making a conscious effort to try to clarify that we see men as allies, every male is not a potential perpetrator, right, we want to make sure that we are embracing men, and bringing them into the movement, because we need them.” Brandt said.

Close to Home

NEIU does not escape from this reality. A recent case in our community involved Ronald Williams library staffer Zachary McMahon, 44, and his partner Melissa Mondie, 43, who were found dead in McMahon’s Ravenswood apartment during an Aug. 15, 2022 welfare check requested by NEIU staff.

The Cook County medical examiner’s office ruled Mondie’s death a homicide and McMahon’s a suicide. Police officers found a weapon at the scene. Mondie’s family alleges that she was a victim of domestic violence.

Brandt said that we need to keep believing the stories of victims and insisting on offering help because these are the most vital things to do, people need to feel that the system and the community cares about them.

She also said that victims need a network that could help them devise and follow up with a safety plan.

The safety plan goal is to keep the victim away from harm and should include steps to follow in case a situation at home or with your partner or roommate escalates. It must have phone numbers from people willing to help and a list of safe places.

Several victims/survivors often find helpful alternatives other than the police department. The Illinois Domestic Violence Hotline received a total of 11,991 calls only in Chicago, with the large majority of callers seeking shelter in some capacity, with information-only calls coming in second.

There are several women-only shelters just in Chicago alone, some include an option for children to stay with the survivor, either in temporary locations or in long term transitional housing programs.

NEIU can also be that physical safe space, the school has resources available to create a safety plan. As mentioned, NEIU has three confidential advisors who are trained professionals ready to deal with the most difficult situations and are able to get you the help you need. You can contact them at any time by visiting the K(no)w More webpage or calling them at the numbers in the textbox. .

The school also offers counseling services to students within office hours and if they are in need of urgent assistance students may call (773) 442-4650, then press “2” to speak with a counselor on call if in crisis.

NEIU recommends staff to use the Employee Assistance Program by searching the ComPsych website or calling ComPsych toll-free at (833) 955-3400.

Extra help is also available at the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-SAFE) and the Chicagoland Domestic Violence Help Line at (1-877-863-6338). This last number is just available for people within the Chicago area.

People in need of support through difficult times can call 988, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. They will be connected there to trained counselors ready to help.

Cindy Barker • Dec 28, 2022 at 11:30 am

Thank you for this article. Melissa was my daughter. We ned to listen and believe the victim. He was able to have a gun because the people he abused didn’t come forward until it was too late. I will spend the rest of my life helping people suffering with domestic abuse.