Your donation will support the student journalists of Northeastern Illinois University's The Independent, either in writers' payment, additional supplies and other items of note. Your contribution will allow us to purchase additional equipment for writers/photographers/illustrators and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Comparing America’s coronavirus response to Spanish Flu, Black Death and smallpox

March 27, 2020

Competing narratives surrounding the severity of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic have led to ideological warfare. However, while pandemics are nothing new, the manner in which American leadership underestimates the potential costs of COVID-19 are jarringly familiar.

As Americans transition into an indefinite “stay at home” mode in an effort to suppress the transmission of COVID-19, many politicians and pundits continue to downplay the tenacity of the novel virus.

Historians 100 years from now may one day pore over video of House representative Matt Gaetz flippantly sporting a gas mask on the House floor days before he voluntarily quarantined himself.

Scholars will reminisce on President Donald Trump’s initial description of COVID-19, which he described as a Democratic “hoax” before reversing his stance. Students may learn about President Trump’s recently-shared plan to oppose the advice of health officials in an effort to “reopen the country” by Easter.

Meanwhile, conservative television hosts such as Trish Regan, Jeanine Pirro and Sean Hannity dismissed the virus, comparing it to the flu before adopting contradicting rhetoric in the ensuing weeks.

“All the talk about coronavirus being so much more deadly [than the flu] doesn’t reflect reality,” said Pirro on the March 7 edition of “Justice with Judge Jeanine.” “Without a vaccine, the flu would be far more deadly.”

A few days later, Pirro backtracked on her own statements by stating, “We are facing an incredibly dangerous and contagious virus that is moving across the world from one hotspot to another.”

As Americans prepare for an extended period of social distancing, the NEIU Independent examines past responses to pandemics and how inadequate or inaccurate responses worsened transmission.

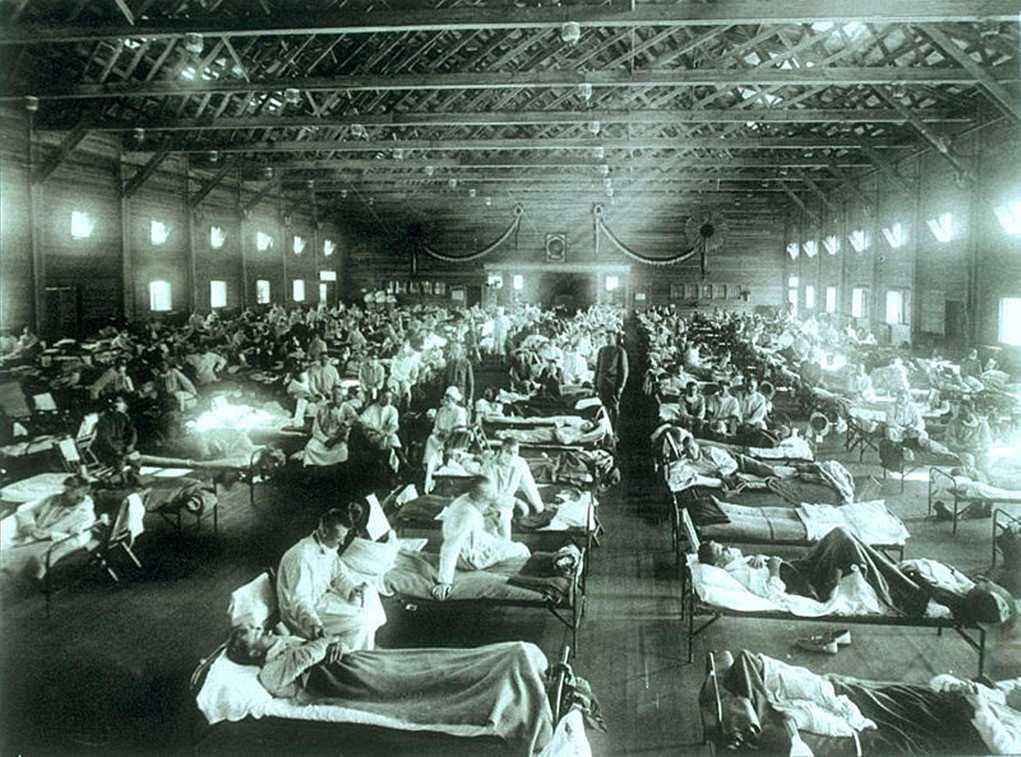

Spanish Flu

The Spanish Flu became the deadliest flu pandemic in history after infecting 500 million worldwide–or one-third of Earth’s population–before claiming between 20 and 50 million lives between 1918 and 1920. However, higher estimates suggest that the Spanish Flu killed up to 100 million, with researchers citing insufficient documentation and poor record-keeping standards as reasons for suspicion.

The Spanish Flu became the deadliest flu pandemic in history after infecting 500 million worldwide–or one-third of Earth’s population–before claiming between 20 and 50 million lives between 1918 and 1920. However, higher estimates suggest that the Spanish Flu killed up to 100 million, with researchers citing insufficient documentation and poor record-keeping standards as reasons for suspicion.

First identified in Europe, the United States of America and various regions of Asia, the path of the Spanish Flu remained unobstructed as the absence of a vaccine compounded upon human susceptibility. During the relatively tame first wave of Spanish Flu, the infected suffered through bouts of chills, fever and fatigue, though a vast majority fully recovered.

The second wave of the Spanish Flu was devastating, claiming victims within hours of the first sign of symptoms. Victims turned blue as their lungs filled with liquid, eventually succumbing to suffocation. Within one year, the Spanish Flu shaved 12 years off American’s average life expectancy.

The flu heavily impacted Spain, inspiring the name “the Spanish Flu.” Unlike its predecessors, the Spanish Flu indiscriminately targeted victims of all ages, killing otherwise healthy young men and women, a group historically insulated from the ravages of pandemics.

Domestic and international responses to the Spanish Flu ran parallel to the United States’ attempts to combat the spread of coronavirus COVID-19.

Municipals ordered citizens to wear masks. Schools, businesses, theaters and other places of public gathering suspended operations as increasingly desperate government officials attempted to blunt the spread of the virus. Government-imposed quarantines were implemented in areas considered high-risk.

Makeshift morgues materialized as the death toll overwhelmed the death care industry. New York health commissioner Royal S. Copeland directed businesses to operate on staggered schedules to suppress the spread of the Spanish Flu.

Nevertheless, the Spanish Flu benefited from a variety of factors.

While the origins of the disease remain unknown–the Spanish Flu is wrongly attributed to Spain due to the nation’s free state media and exhaustive coverage on the disease’s progression–researchers believe military units carried the disease from one military base to the next during World War I. Additionally, infected soldiers returning home passed the Spanish Flu to the unsuspecting general population.

World War I also left many countries short on physicians, creating an environment for the advantageous virus to rapidly spread absent of intervention.

Meanwhile, the first licensed flu vaccine was more than two decades away, placing the relatively few healthcare workers dispersed throughout America in tragically compromised positions. Many nurses and doctors contracted the virus, further depleting an already scarce resource.

Initial efforts to treat symptoms were feeble, ineffective and potentially counterproductive. For example, physicians briefly prescribed 30 grams of Bayer-patented aspirin to alleviate symptoms, an amount since deemed toxic.

Philadelphia Director of Public Health and Charities Dr. Wilmer Krusen attributed rising fatalities to the “normal flu,” leading the city to move forward with its Liberty Loan parade, where tens of thousands of attendees became unsubscribing hosts to the rapidly-spreading disease.

St. Louis mobilized a quicker response, expediting decisions to manage the transmission of the disease at the expense of the city’s economy. As a result, the Spanish Flu claimed one-eighth fewer lives in St. Louis than it did in Philadelphia.

After a long, arduous battle that claimed tens of millions of lives, the pandemic disappeared once everyone affected either died or developed an immunity. In 2008, almost ninety years after the first wave of the Spanish Flu, researchers discovered a group of three genes that enabled the virus to evolve into bacterial pneumonia.

The Black Death (Bubonic Plague)

Like the novel coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, the Black Death originated in China before traveling westward along the Silk Road and landing on Genovese ships which later docked at the Sicilian port of Messina.

The plague–which Kipchak khan Janibeg once weaponized by catapulting infected corpses at his enemies–arrived in Europe in October of 1347 before carving a four-year path of destruction throughout the continent, claiming 20 million lives, or approximately one-third of the European population. Overall, between 75 million to 200 million Eurasian lives were lost to the plague.

Italian officials identified trouble immediately, ordering ships arriving from the Black Sea– which were carrying dead and infected soldiers riddled with black, pulsating boils that ejected blood and pus–to depart the docks.

Unfortunately, it was too late. An infectious fever caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis began indiscriminately infecting anyone unfortunate enough to come in contact with it. Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio described the uncertainty and fear paralyzing the public as contraction became a near inevitability.

“The mere touching of the clothes appeared to itself to communicate the malady to the toucher,” wrote Boccaccio.

The disease traveled pneumatically and through the bites of rats or fleas which, at the time, were found everywhere, particularly on ships and other water-bound vessels.

The plague also handicapped commerce, with doctors shuttering their doors to patients, traders suspending transactions and priests denying the dead their last rites. Europe endured a wool shortage, as the unforgiving grip of the Black Death tore its way through sheep and other livestock, including cows, pigs and chickens. Those fleeing the congestion of large cities were greeted by the stark reality that the plague commuted to the countryside, uncritical of its prey.

Resistance against the plague was woefully disorganized as officials attributed the Black Death to divine intervention.

Medical professionals grasped at any explanation to explain the rapid, efficient nature of the disease as others sought to win God’s favor by repenting for past sins, hoping to appease vengeful deities. Physicians resorted to blaming the Black Death on the malice of an evil fog as communities adopted ritualistic measures such as altered sleep patterns to ward off transmission.

As entire monasteries were wiped out and villages abandoned, faith in religion rapidly dissipated as followers grew to realize that organized religion was helpless against the plague. Labor shortages tied to the destruction of the Black Death also revolutionized serfdom, as once-authoritarian Lords were forced to appeal to serfs suddenly at liberty to choose who to work for and where to work.

Smallpox

The origin of smallpox remains a topic of debate. However, no remaining evidence predates the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570 B.C. to 1085 B.C.). Furthermore, some historians attribute two subsequent plagues–the Plague of Athens and the Antonine Plague of A.D. 165 to 180–to smallpox, though such conclusions remain in speculatory stages.

Smallpox reached Europe around the 6th century and brought with it a violent fever accompanied by pus-filled blisters. If patients survived the fever, the blisters scabbed over before disconnecting from healed wounds.

The most common strain of smallpox claimed the lives of approximately 30% of its patients. In the Americas in 1520, smallpox carried a catastrophic effect on a population lacking immunity, with historians theorizing that the disease reduced the indigenous populations of both North and South America by up to 90%.

Many survivors were blinded and disfigured while those who escaped unscathed were called upon to tend to patients as they were unable to contract the virus twice.

For a long time, public helplessness abetted smallpox’ disastrous journey. However, unsuccessful attempts to quell the disease’s progression eventually led to the world’s first vaccine.

In 1796, English physician Edward Jenner injected pus from a milkmaid infected with cowpox, a close relative to smallpox, into a healthy 8-year-old boy before closely monitoring the immunization process. Jenner’s vaccine is credited with causing the downfall of smallpox, with then-President Thomas Jefferson writing, ““Future generations will know by history only that the loathsome smallpox existed and by you has been extirpated.”

By 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an global immunization initiative to internationally eradicate smallpox. On May 8, WHO declared smallpox eradicated.